Susan Kelly Power

"Just outlast, learn to outlast people. That's why we're still here, as Native people, we learned to outlast. They come and the government decides, "You're going to do this and you're going to do that. This is what you should be and shouldn't be." Just wait. We just sit there and smile at them. They'll go on, they'll get tired. Patience."

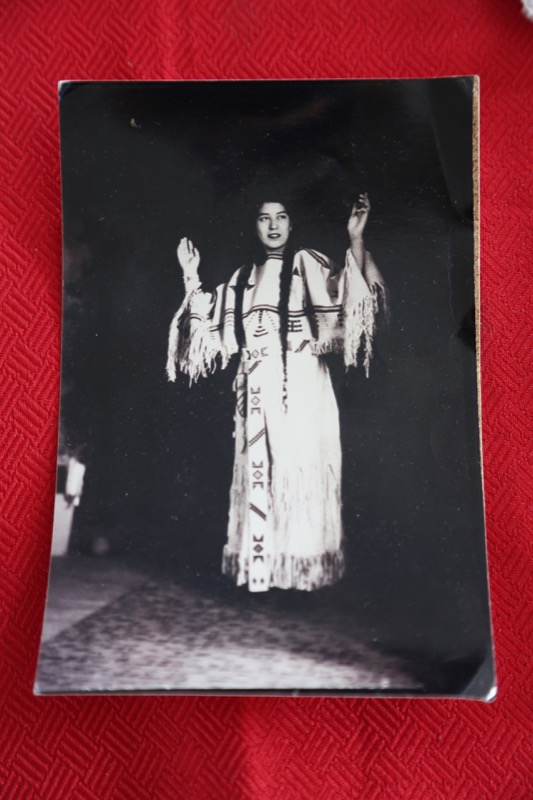

I can't remember exactly how I found out about Susan Kelly Power, because it was at the end of a long and winding web search. Eventually, I read about a woman associated with the Newberry Library, a research library in Chicago, whose last name was Power, one of the themes of this project. Susan is a Sioux from a reservation in North Dakota who moved to Chicago in 1942 and was one of the founders of the American Indian Center of Chicago. At 91, she's feisty, funny, and full of stories and concerns. Our interview was more of a conversation, added to by a few visitors, and continued on during the video shoot. Her South Shore high rise apartment on the lake ("I can assure you I'm the only Native out here") is full of books, photographs, and art, reflecting her love of history, literature, and family. She's perturbed when people are ashamed of their ancestors, she recognizes that telling the truth can make you unpopular, and she's not ashamed to speak her mind. Our roughly four hours together included a range of emotions and she remained generous with her conversation and time. When I explained this project to her, she responded "Mind over matter...I hope a million dollars will fly my way and I'll grab it." She's a woman of words, gathering them, sharing them, writing them, and using them, so even though I originally didn't want any of the video portraits to be in the form of an interview, conversing with her on camera made sense. Susan's portrait was a bit impromptu, so we improvised with the space and with her cat, Rosie. Ultimately, her collection of memorabilia and art led me to the idea of allowing her stories and gestures to illuminate one of the centerpieces of her apartment.

Lori: I found out about you through the Newberry Library's website. My husband used to work at The Newberry, so I followed the lead when I came across your name as part of research fellowship.

Susan: Yeah, they named a fellowship after Dr. Helen Tanner and myself. I'm proud of that. She was a wonderful scholar, and we were good friends. We had shared interests in history. Somebody created this fellowship with both of our names. Once in awhile, I'll get a call from someone saying, "Thank you! We know Dr. Tanner's gone, but we want thank you, because this got us through."

[At this point, Susan's friend Stephanie leaves the apartment and Susan goes on to explain her living situation...]

She lives down the street, but she stays here most of the time. Which is alright with me, because I don't like to be alone. My mother had eight children and there were seven of us. We were always a big family. Sitting around the table, always had a lot. We had just three rooms, but we had a big family. It was nice. So, I don't like being alone.

Are a lot of your siblings still around?

My siblings are all gone. I'm the last one. I'm 91, so you know, some of the older ones... I was just in the middle. The younger ones are gone and the older ones are gone. I miss them very much. I had wonderful, wonderful, sisters and brothers. My oldest sister is buried in Minneapolis, Minnesota where her family settled. The next sister's buried in the reservation, in a little cemetery by my mother. And then me, I'm here. The next sister's buried on Fort Berthold Reservation, because she was married into the three affiliated tribes. My brother was married into another tribe, another group out in Seattle, so he's buried out there. My other brother was buried at home, he was married to somebody on the reservation. My baby brother was killed in Korea. My mother had him buried in Arlington National Cemetery. So, we're all spread out. And I've lived here a lot of years, this is my 40th year here.

It's a great view. We used to sit right out there and swim. My daughter and I were swimmers. We'd just swim all the way over to those trees and back. We'd swim out. You go out a little past there, it gets pretty deep. We had a little tiny bungalow over here, my husband and I hadn't been married very long. I was telling somebody, we saved our first thousand dollars. Back then, you could use that as a down payment. We bought this little bungalow not too far away. Then when he passed away, we were just married going on 12 years. I planning on was going home, but my daughter was the first Native to be at the lab school. She got into the lab school because I was working there at the law review. She said, "Mom, could you wait to move until I finish school? Because I like the lab school."

She said, "Mom, they don't care what nationality you are, if you're rich or poor. It's mental. They're always in competition with you mentally. So, I know how I'll get along, I'll just out-do them." And she did. She got along and she loved it there. So, I stayed here. And I thought, "When she goes off to college, then I'll go." She said, "Mom, can you stay 'til I'm through with college?" That was seven years. I was here. Then finally, I thought, "Well, shoot. Everybody's gone now. I'm still here." I'm the last founding member of the Chicago American Indian Center, which is going through turmoil again. Every organization does, though. You start out with very neat and good intentions for your people. They're just coming into the city, they're becoming urban Indians. I promise, we founded the first of its kind in the nation. We've gone through ups and downs. We've had some jerks who ran it, who think they know everything. I just said, "Just wait them out. We'll wait them out." People get upset, "You've got to do something, Mrs. Powers!" "No, we'll wait them out. " I said, "This is the fourth or fifth group now. We'll outlast them." Sure enough. I said, "See, we outlasted them."

And we'll go on just smoothly, and then we'll get another one that'll decide they know everything. Just outlast, learn to outlast people. That's why we're still here, as Native people, we learned to outlast. They come and the government decides, "You're going to do this and you're going to do that. This is what you should be, and shouldn't be." Just wait. We just sit there and smile at them. They'll go on, they'll get tired. Patience.

What brought you to Chicago in the first place?

I didn't come on my own. My mother sent me here. My oldest sister was becoming an Army nurse. The war was on, this was 1942. The next sister was waiting for the Marines to open up, she wasn't going to be an ordinary sailor or soldier, she was going to be a Marine. The Marines were opening up to women. As soon as they opened up, she went into the Marines. First Marine from our reservation, female Marine. So, I was the next in line. Momma's old friend was married to a white man, who was a pilot for American Airlines. She was sick and she was very depressed. She said to my mother, "I have three sons and they're all overseas," because the war was on, "You have daughters. Loan me one." I was the only available one. Back then, you didn't disagree with your parents. You're going, you go. That's why I came here. With the intention of just being here through her problem and then going home. Then, of course, I stayed.

Why did you stay?

First of all, I could see there were opportunities here. Jobs.

[At this point, some friends from the American Indian Center and the Mitchell Museum of the American Indian showed up and we all shared in the conversation. They were stopping by to hear some of Susan's stories, borrow some photographs and art, and prepare for an exhibition.]

Kathleen: In the photograph with your mother in the hallway, who are the group of men that she's with?

Susan: That is her council. Her tribal council.

Nora: There are a lot of them.

Susan: Yeah, well, remember, we have all of these towns and each one has it. She was the first native woman to be the head of a tribe. And she got along with them very well because she didn't act superior to them. She didn't have to, she knew that being a woman, she was! Because the women have the children! No, I'm only making that joke because somebody told her that.

Lori: How does one get to be on the council?

They have to elect you. It used to be that you were automatically a leader, doing things for your people. You were helping automatically, and then, eventually, in the 30s the government started the tribal councils. My mother was elected and no one ever came near her because she was a person that loved her people and she cared. If she had a slice of bread left, it was divided up. She was very generous and she was really the old way. Just think, here is this strong woman who had gone to Carlisle Indian School and stayed there because they knew they didn't come home each year. They stayed there. She stayed there too. She graduated and she loved Carlisle. Some of these people who write this nonsense, they don't even know because my mother was the first one from our reservation. She loved it. At the NCI convention in Denver, we'd have all the old Carlisle graduates, and if some people had listened to them talk how they love Carlisle, they would see. That Carlisle was bad is somebody else's theory, probably some ... Excuse me, I don't mean you, but some white person came in and felt sorry for us and thought that we should've been upset that they did this to us. They add a lot of that nonsense later.

They all loved Carlisle. You never find anyone who hated Carlisle. My mother's happiest memories were at Carlisle. When she was lonesome, she'd sing the old Carlisle song to herself. She'd be singing it, with good memories. It was good to see, then, that Jim Thorpe was there. He was there at that time when they had this last gathering of Carlisle graduates. He was so nice. I was sitting there by my mother with the Old Carlisle graduates who were singing together, this National Congress of American Indians, of which I'm one of the founding members. I'm proud of that. Didn't know I was part of anything. I was just young, going along, you know. I was sitting there and my mother was sitting by me and then Jim Thorpe came up and with his foot, he tapped my mother's foot. He said, "Josephine here taught me how to dance. Didn't you?" And she said, "I guess I did." And he said, "Let's show them." He took her up by the hand and they hummed some song, an old Carlisle song, and they waltzed around.

[Susan continued to tell stories about her mother:]

But my mother...It was hard for her daughters because when you were raised by a mother who went away to school at 9 and came back at 20 from Carlisle, became a leader, the first tribal leader, and raised her children alone, and they all turned out good... God bless my father but he couldn't take the responsibility of children.

The times were hard. You couldn't get a job no matter what, no Indian can get a job on the reservation. She raised us all well, to be honorable. She had six in the service, my baby brother was killed in Korea. Indian natives are very patriotic. We may not love the people who run our country but we love our country. I remember, December the 7th, I came home from church and everybody was running around and very few people had radios, they had the old battery radios, and they said, "Josephine, Josephine!" Shaking the screen door. "We're at war!" And mama said, "We are? With whom?" "With Pearl Harbor, but I don't know where that is." "I don't know what country that is, do you Josephine?"

She said, "No, but we'll find out." She said, "Well, Mr. Jacobson has all those big atlases and stuff, we'll find out." And so we knew. And then, immediately the next day, Frank Fiske, who was our town photographer, he's a famous photographer by the way, you'll see his name if you ever see any photos of Dakotas. Anyway, he had the recruiting office open right away. Every Indian from eight years old till 80 was up there, going to fight in the war. They're very patriotic people. If it's a just war, that was a just war where they were out to destroy us. We had to be careful because we were immediately returning our hatred to our German neighbors and my mother reminded us. My sister and I said "I'm not going to play with them" and she stopped us on our tracks and reminded us. Very fair woman.

[Susan continues, expanding upon the history of the American Indian Center of Chicago:]

The Center is the first of its kind, and we had people that used to come in from San Francisco, New York, Cleveland, who came in to talk about our Center. There'd never been one formed in the city. See, Indians were just relocating to cities around World War II. We were so proud that they were coming there, that we were doing something right. You know that other people had sent the delegation. That was something for us.

How many of you would gather around the time the Center started?

Oh gosh, the original, I would say there are couple of hundred, but not all times. There were always more than 50 that would be gathering at the old place. First, we met at Eli's, we didn't have a place to meet. We all just had rooms, we used to get a room at some widow's house and we'd stay there. We didn't have apartments. And then Eli Paulas worked in a bakery, so if we had no food, we always had cakes. He would always bring stuff from the baker because the bakery people liked him. We would meet in the bakery, because his landlady was nice white lady, real nice, and she had a nice big clean basement. We have no place to meet so we'd go down and meet.

How did you find each other?

We'd find each other. We'd walk down the street. I was walking on State Street once and this pigeon-toed woman was walking, Indians are kinda pigeon-toed, the old timers are kinda pigeon-toed, because, as they say, they used to walk on paths, I don't know. I think we're just naturally pigeon-toed. But anyway, I said to her, "What tribe are you?" That's the first thing we hear. What tribe are you? And she said, they didn't say Ho-Chunk then, "I'm Winnebago." I said, "I thought you were." And we were friends until her death.

In regards to finding a community, what would your advice be for young people today?

I would say to them, as long as you know [who you are] and your ancestors or your parents told you, then don't ever doubt them and just learn about them, don't try to prove it to anybody. Don't go to the Center and try to prove it and don't even worry about it, because you know, that's what counts. Because my daughter had that trouble too, you know, she could pass for a little white girl, but she knew and she didn't care. [To those who doubted her background] she'd say, "Oh, is that right? Go ahead and talk to my mother." And they said, "Oh, that's your mother?" You see, you don't know. And you have to be nice to people.

And this is what galls me, remember this. A lot of non-Indians will come in there and like us as people and just because they can't prove [their background], and they're not even trying to say they're Indian, they just want to be with us. Be glad somebody likes us enough to want to be with us! I always think that. Let them be part. Gosh, some of our best friends have been people of that category. I mean, I just stop and think of Dr. Leonard Bormann, my gosh, what we have done without Dr. Borman. He was Jewish. A very, very good man. Matter of fact, when my husband passed away, the first person I called was Dr. Borman, a good man. I miss you, Lenny! And I know if they try to put him in another part of heaven he'd say, "Over there, over there!... Benny Bearskin is over there".

[We then moved over to the couch in the living room for the portrait video and we kept on chatting]

So, what do you do with your days?

Most of the time, I write. I write the history of the Chicago Native community, history of the Two Bear family, and the history of whatever I feel like writing about that day. I write about something interesting that happens, pertaining to Native culture, if possible. I'm writing memoirs, more or less memoirs. I like to write about important incidents, like say somebody did something pretty noble at the Center, and I don't want it to be forgotten, so [I] write [about] it. You know, some good people there did something, most of them did nothing, but the good ones who did the work, nobody even remembers their names. I'd like to get pictures and have a memory wall there, and have pictures starting with Bob Reitz and Dr. Borman and Dr. Tax, three white men who made it possible, and nobody even knows their names. If you're going to put my picture up there, you're gonna put it up after you put their pictures up.

Do you think your work with the Center and with the community is different because you're a woman? Do you think about that at all?

No...My people don't ... we're equal. We've always been equal, some are superior and some aren't you know. I've never had a problem with that. Other tribes do, but not mine.

A question I've been asking everyone: When do you feel the most powerful?

[Sarcastically to the cat] When I'm going to open Rosie's food and I decide to not feed her and I'm powerful because she will die if I don't feed her. Right? She's looking and feeling sorry for herself.

No, I feel most powerful when I look out that window at that lake and I believe in The Creator, and I believe that anybody who doesn't believe, there's somebody more powerful than himself, ought to be ashamed of himself. They ought to go jump in the lake head first and stay down there, because who could create something so beautiful, and I'm grateful that I was taught to believe. Usually people do whether they go to church or not.

When do you feel the most powerless?

Well, I'm wondering if I'm going to be able to pay the increase on our new assessments. Everybody feels that way, when there's an increase in our assessments. I'm probably going to have to sell and move. I can't afford it. But it's all right. I've lived here long enough. I own the apartment outright, but it's a corporation. We own our apartments privately. We have to pay for them before we own them, before we can even move in, and then after that, we have to pay assessments which is for the upkeep of the building, the taxes, and whatever the city throws at us and all that. I'll have to sell. I'll go buy a lotto ticket, I might win.

Where would you move to if you had to move?

Home. I always wanted to go home. Except I'll miss Chicago, I like Chicago. There's a lot of good about it. I like the variety of people. When I go home, I just see Indians and some white people but I like to see Asian people and Black people. But you know, you look at the Middle Eastern people that live over in Mayor Daley's neighborhood. They're all hardworking, good people, and that's who I used to work with, so I got to know them well. I really like them and they love this country. When they came here, they just didn't come here to take advantage of it. They love this country. They came here of course for livelihood and all of that, but they love the country. I like people who love our country...

...and Rosie doesn't love anything but her fat little grey stomach.